“Here we are now, entertain us,” if we could choose one phrase that would describe the modern learning process, this quote would suit best. Games have been present in education for a long time: role-playing games aimed at preparing students for real-life scenarios have been used in a wide range of fields — from the second language teaching to corporate trainings, and various types of simulators are starting to gradually replace driving lessons.

Turning to this strategy in e-learning would have been unavoidable. Yet, gamification is not equal to games per se. It is referred to as the “use of game design elements within non-game contexts” (Deterding et al., 2011, p. 1). The central idea is to take the “building blocks” of games, and to implement these in real-world situations, often with the objective of motivating specific behavior within the specific situation. It is widely accepted as promising and is taken quite seriously by the e-learning industry: by 2018, gamification in e-learning will grow to a 5.5 billion USD global market.

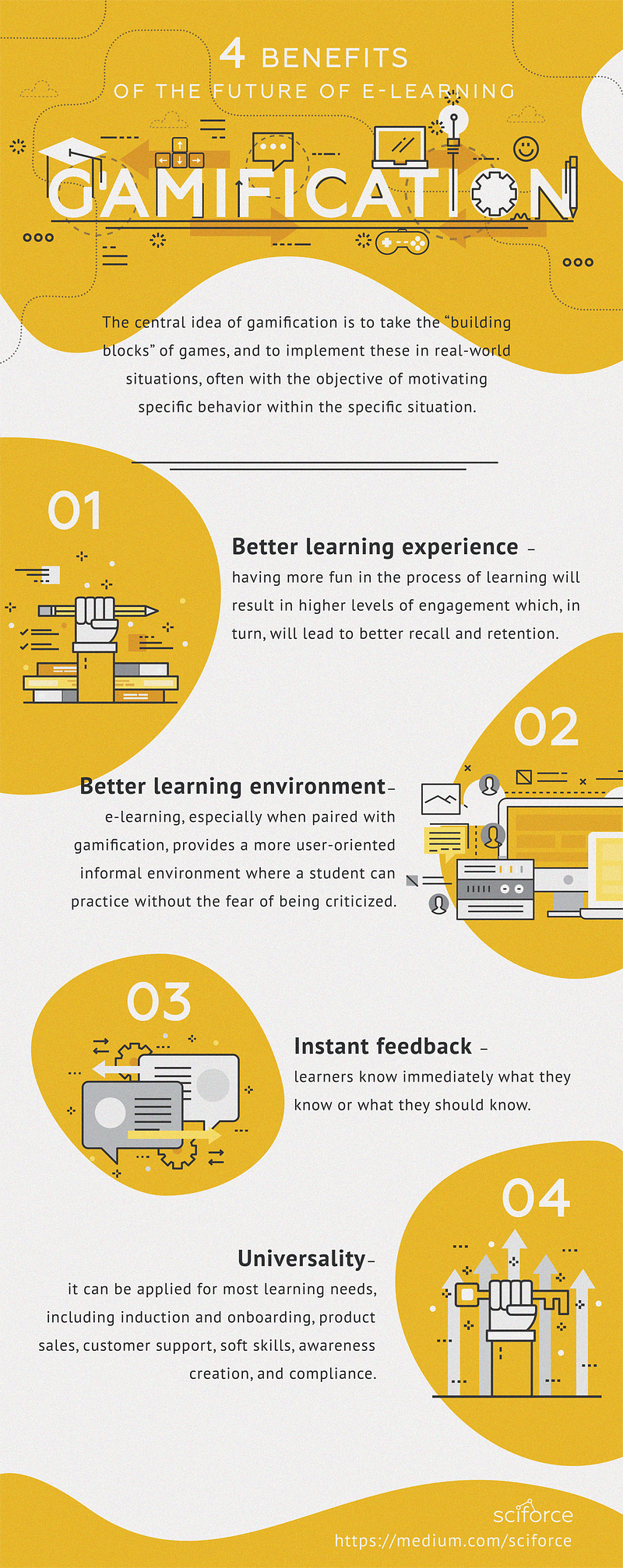

1. Better learning experience — having more fun in the process of learning will result in higher levels of engagement which, in turn, will lead to better recall and retention.

2. Better learning environment — e-learning, especially when paired with gamification, provides a more user-oriented informal environment where a student can practice without the fear of being criticized.

3. Instant feedback — learners know immediately what they know or what they should know.

4. Universality — it can be applied for most learning needs, including induction and onboarding, product sales, customer support, soft skills, awareness creation, and compliance.

As we can see, these benefits are chiefly related to increasing learners’ engagement which helps achieve higher levels of retention and ultimately remembering.

In 1956, Benjamin Bloom and his fellow educational psychologists developed a classification of levels of educational behavior: cognitive (knowing), affective (feeling), and psychomotoring (doing). At the cognitive level, Bloom suggested six levels: basic knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation (Bloom et al. 1964). In the 1990ies, the taxonomy was updated to reflect the changes in the society and the relevance of the skills in the future years. The updated taxonomy defined the categories as remembering, understanding, applying, analyzing, evaluating, and creating (Anderson et al. 2001).

Simulation and educational games are quite effective for the three lower levels of the taxonomy, contributing to motivation, emotion, and attitude.

To give the answer how we can increase such motivation and engagement by deliberately addressing human needs, educational psychologists turn to motivational theories that explain the success of gamification by addressing the human needs of self-fulfillment, competition, and independence.One of the theories that has been successfully applied in the context of gamification, is the self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2002) that postulates three basic psychological and intrinsic needs:

The need for competence assumes that every human strives to feel competent when deliberately influencing the environment they interact with.

The need for autonomy refers to psychological freedom and to volition to fulfill a certain task. In this context, autonomy refers both to (a) decision freedom, which implies being able to choose between several courses of action, and (b) task meaningfulness, which implies that the course of action at hand conforms with one’s own goals and attitudes.

The need for social relatedness refers to one’s feelings of belonging, attachment, and care in relation to a certain group.

Research (Sailer et al. 2017) suggests that the popular gaming elements such as badges, leaderboards, and performance graphs positively affect competence need satisfaction and perceived task meaningfulness/autonomy. On the other hand, introduction of avatars, meaningful stories, and teammates positively influence social relatedness creating a sense of belonging to a certain group.

With gaming elements being effective primarily for lower levels of the cognitive domain, the question remains whether gamification can be used to tackle more complicated and abstract entities, like advanced-level grammar or computer programs and algorithms.

Studies suggest that even for advanced online courses, the key factors are a learner’s initial interaction with an online platform (Tyler-Smith, 2006) as well as a learner’s control (Chou & Liu, 2005) and motivation (Keller & Suzuki, 2004). Here again, engagement and motivation play the decisive role. At the same time, there is no evidence of increase in the performance, tackling the upper cognitive levels — analyzing, evaluating, and creating — which are crucial for programming.

Besides, learning styles and, therefore, the attitude to gamification in learning, varies depending on the type of the personality, as well as on the culture and environment. Gamification is a trendy phenomenon that probably never will attract all.

Nevertheless, there is definitely a need for e-learning to address the issues of boredom and loneliness in online platforms. And in this case a badge or a leaderboard, even without being an ultimate goal for anyone, can be used as a fun gimmick creating a positive attitude in online courses, including the most complex and challenging ones.

References

Anderson, L. W. and Krathwohl, D. R., et al (Eds..) (2001) A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Allyn & Bacon. Boston, MA: Pearson Education Group.

Bloom, B. S., Mesia, B.B., and Krathwohl, D. R. (1964) Taxonomy of Educational

Objectives (two vols: The Affective Domain & The Cognitive Domain). New York. David McKay.

Chou, S. W., & Liu, C. H. (2005) Learning effectiveness in a Web-based virtual learning environment: a learner control perspective. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 21(1), 65–76.

Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., & Nacke, L. (2011) From Game Design Elements to Gamefulness: Defining “Gamification”. Paper presented at the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference, Tampere.

Keller, J., & Suzuki, K. (2004) Learner motivation and e-learning design: A multinationally validated process. Journal of Educational Media, 29(3), 229–239.

R.M. Ryan, E.L. Deci (2002) Overview of self-determination theory: An organismic dialectial perspective in R.M. Ryan, E.L. Deci (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research, University of Rochester Press, Rochester, pp. 3–33

Sailer, M., Hense, J.U., Mayr, S.K., Mandl, H. (2017) How gamification motivates: anexperimental study of the effects of specific game design elements on psychological need satisfaction. Comput. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 371–380.

Tyler-Smith, K. (2006) Early attrition among first time eLearners: A review of factors that contribute to drop-out, withdrawal and non-completion rates of adult learners undertaking eLearning programmes. Journal of Online learning and Teaching, 2(2), 73–85.